Crime Novel

New novel - The Holocaust Denier (2012) A Faustian journey, The Holocaust Denier is set in Melbourne (or New York or Tel Aviv or London) with interweaving themes of police culture, Holocaust denial, ‘Correctspeakers’, 'Incorrectspeakers', home renovations, crime, and multicultural treats and multicultural sighs of relief. Purchase through bookstores or Amazon. Trevor Poulton thdnovel@hotmail.com

Holocaust denial ... the crime ... the judgement ... the price

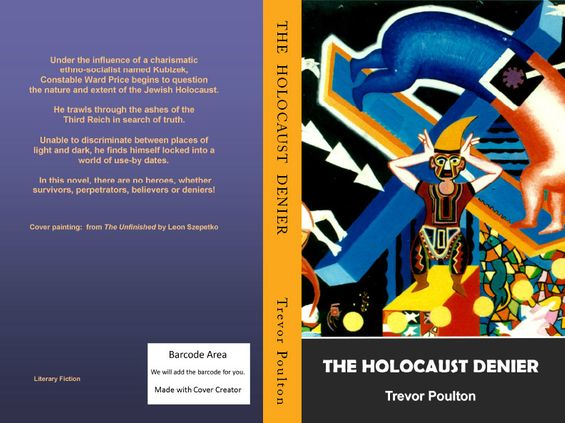

THE HOLOCAUST DENIER

By Trevor Poulton

Purchase through Amazon (paperback or kindle)

or

from a local bookstore

Contact the novelist: poulton@labyrinth.net.au

For some readers it is a crime novel, for others it is Faustian fiction, and for others a forewarning of the extinction of the ‘Killer European’.

Under the influence of a charismatic ethno-socialist named Kubizek, Constable Ward Price who is a member of the Victoria Police Force begins to question the nature and extent of the Jewish Holocaust. He trawls through the ashes of the Third Reich in search of truth. Unable to discriminate between places of light and dark, he finds himself locked into a world of use-by dates. In this novel, there are no heroes, whether survivors, perpetrators, believers or deniers!

The backdrop is police culture, home renovations, ‘Correctspeak’, and ‘Incorrectspeak’. Set in Melbourne, it may be one of the first novels to explore in any depth the troubling inner life of a Jewish Holocaust revisionist/denier spiraling downwards, without the stereotypical Hollywood simplistic approach of branding 'deniers' as criminals or sociopaths. He has done a deal with the devil. Questions are asked, and answers are found and lost, with one of the themes being denying death itself.

EXTRACTS FROM 'THE HOLOCAUST DENIER'

From Page 3

‘Sorry about the rough ride,’ Bullock said to the driver, and they cleared off.

The police radio was unremitting with one job allocated after another. This was Carlton, a suburb of spruikers waving menu flyers about like machine guns and the occasional mopping up of tomato sauce in back rooms, and at tables on the promenade slit smiles would be sucking in pages of Il Globo while sipping Italian espressos. Ward had learnt pretty quickly on crime beat that Carlton was the badlands of Aussie pizzas, upstairs poker games and the Carlton Crew double-parking bulletproof Mercedes Benzes in Lygon Street. But he had also discovered that it was a suburb of great depth, with an art-house cinema complex, alfresco cafés, wine bars, playhouses and bookshops, plastered with time-honoured posters. From cover to cover it was an album of renovated heritage Victorian terrace houses and snapped wrought-iron love affairs, yawning sash windows and fatigued verandas. Local history told that it has been the residence of many a broken playwright, author, filmmaker and politician, with the centrally located cemetery operating as a publishing house of vain epitaphs drafted by the dead. Carlton, situated on a plateau snubbing Melbourne’s regulation glazed plazas and skyscrapers, its football stars have flown higher than all its tall buildings – Jesaulenko, you beauty! It was a stylish place in summer with a shade hat on it, where you could sip a glass of beer or wine under European plane trees while burglars pedal by. It was a necklace of emerald squares that were a home to deros, drunken poets and drug addicts. And it was an overspill of overworked academics at the university, and overseas students strategising for permanent residency. It was a precinct where coppers write up traffic tickets or are out of the divvy van pissing on with licensees at the back of hotels or screwing single mums and separated dads in the housing commission flats.

The earth beneath the house

An Anglo-Saxon Welsh working class heritage was the foundation for success for Dr William Price, the patriarch of the Price family. He was a corporate lawyer who possessed a strong work ethic, a great sense of individualism, and self-reliance. Dwelling at the top of the societal hierarchy, he felt comfortable devising a formula for success for his progeny. It would parallel his life journey.

An all-rounder, his eyes would twinkle with an assortment of colours, for he could be in a suit and tie one day, and next in a drenched singlet and worn-out trousers with a busted zip, digging post holes in the backyard. Or he could be revelling with his mates in the outdoor BBQ area. Or in the dining room, verbalising feats beneath crystal chandeliers with groomed guests paying much attention to him, for mostly he had things to say that were important. It was said that you could get a better legal opinion out of Ward’s father before he had time to spill cigarette ash on his suit than you could get out of the Attorney General in six months. His father was a short, powerfully built man who did not rely only on his magnificent intellect to cause a sensation, as when, at the invitation of his friend the Prime Minister of Papua New Guinea, he demonstrated that he could deposit five burly bodyguards into a swimming pool without getting wet himself!

During the first decade of his childhood, Ward came to know telling scents of his father: salt, fecund earth,

nicotine, shaving cream, and musty memorabilia relating

back decades. There was a replica of the family coat of arms hanging on the wall of his father’s study next to his law doctorate and his Member of the Order of Australia certificate. The coat of arms had an ancient ship floating on wavy, azure water,

a red rose and two curved crosses that looked like the markers on Nazi fighter planes out of the World at War video game. Ward was told that the crosses indicated the importance of the town of Price as the centre of an ecclesiastical district in England.

The crest wreath was blue and gold, and beneath it the motto was in Latin.

‘What does the Latin say again, Dad?’

‘It translates, May we flourish beneath the cross. I found it in a bric-a-brac store in London, son. If you work hard and keep studying, then you will be successful. You must study long and hard if you are going to be a doctor like your Uncle Mark.’

‘Yes, but I want to be a lawyer like you, Dad.’

‘Tom will be the lawyer,’ his father insisted having already dictated the future profession of each of his six, tender children as they queued up before him one night. What power has the father!

The young Ward would often gaze at the coat of arms with a developing sense that the past is full of memories yet to be experienced, that it is just as mysterious as the future, and that one can travel either way in space and time on a mystical cross.

At an early age he laboured alongside his father, discovering textures of building and garden materials. He would press down on planks of hard and soft wood with cubbish hands while his father measured and sawed lengths of timber for his renovations. And they would mix sand and cement in a crusty wheelbarrow swelling with water from an irrepressible hose, and they would spread mountain soil trucked in from a nursery on garden beds with the soil caving in on envious weeds. Early on, his father set up a workshop underneath the double-storey, twenty-two room Edwardian house in Mont Albert in which the family lived. And the father and the faithful son would excavate expansive storage spaces united with relays of light bulbs and quivering cobwebs strummed by tunnel winds, and they’d roll out concrete paths between great pillars of bricks supporting the boarded sky. They would erect racks and pour cement platforms that could be narrow footways. For, together, they were building a city beneath the house. Often his father would spend as much time reflecting on their enterprise as doing the work, and Ward, half the size of his father, would also reflect but on a littler scale.

And during many an evening, Ward would pass the doorway of the study with its plush folds of curtains and glossy wainscot, and he’d spot his washed father reading reports and making notations, with a continuous cigarette merely dangling from his lips, the smoke never being drawn into the lungs. And for several winters, mallee roots blazed away in the fireplace with Ward sitting on sanguine carpet, reading books and making scribbles of his own, and often they would play the game of chess which his father had taught each of the boys and the girl. At the age of ten his father dubbed him the Student Prince, and the child felt that he should grow into the image of the father, despite his father’s resistance to him becoming a lawyer.

Beyond racks of recycled timber, the earth beneath the house tapered upwards towards the floor joists of the sitting room, and then dropped down into a moist valley with several small moons of light passing through a vent, and the land ascended again to a plateau accessible only by rusty pipes, extinct wires and diminutive creatures with eyes that flash. But to the left of the artery of this underground city, above one of the raised concrete footways, there was an opening in a single brick wall, a dwarf doorway accessing an empty room engulfed in darkness, and beyond that he did not know what. One day, Ward set out to explore the outskirts of the underground city where he would be confronting bogeymen, the fatal powers of unleashed electricity and gas, and ferocious rodents and spiders that had to date kept him prisoner within the excavated regions. He packed a torch, paper to draw a map, a bundle of nicked keys in case he came across sealed doors, a bottle of juice, and a bag of lollies. He crawled across a dirt floor and wiggled through a narrow break in the foundations where his torch illuminated a mass grave of green bottles with their necks sniffing the air. He could hear footsteps of inhabitants thumping overhead. His knees and elbows were soiled and he was shivering from the cold. And he could hear a waterfall emanating from a toilet or bathroom. At the end of the passage there was another opening. He crawled through it, tumbling onto a dropped floor. He flicked his torch about, discovering a cellar with food tins, posters and cushions. And his eyes opened wide as he stared down a hairless transparent human head encircled by candles and congealed wax. It was the life-size anatomical model he had received for Christmas that had recently vanished from his bedroom.

On resurfacing, he approached his older brother, Tom, who revealed that a year previously he had also undertaken the subterranean journey, and that the refurbished cellar was a place for him and his mates to hide from Nazi elders. As for the theft of the head, Tom said, ‘Sorry Frecks, I took it to scare off ghosts. There’s no room in the tomb for the dead,’ and he laughed. As Ward never wanted to become a doctor, he was content for his head to hide in the cellar where it could develop a personality.

His parents had done well by providing the children with a rich environment in which to flourish. Playing on the steep terracotta roof of the house with its terrain of peaks and gullies, using any one of the chimneys for balance, they could view the entire bumpy chequered quilt of the greater metropolitan area of Melbourne that spread to the coast, sprawled along the foothills of the Great Dividing Range, and heaved into the northern plains with an embroidery of housing estates. They had been gifted with one of the city’s best double-storey rooftop views.

But as the siblings reached adolescence, disillusionment began to creep into their daily affairs. Their father would ambush them. ‘Why aren’t you studying? You’re all useless,’ he would say to the boys, sparing the girl. And by the age of thirteen, Ward had matured enough to legally decipher a pattern of domestic violence within the mansion. There was much hostility between the father and the mother which would break out into physical confrontations initiated from either side. And there were other permutations of violence. A brother threw a rock at Ward’s head because he wouldn’t turn his music down, and the high velocity object had near missed him. He could have been manslaughtered. On one occasion, his father had come home drunk and began arguing with Ward’s younger brother, Daemon. His father drew a billiard cue from the house armoury and struck Daemon in the face, splitting his upper lip. Times like that Ward felt that it would be better to be below ground than above it. But it toughened Daemon. A year or so later, he would not infrequently come home with blood on his school shirt. A formidable street fighter from a dysfunctional upper middle class WASP family, Daemon had become a suburban mall badass.

Of school mornings the boys would lie listlessly under their doonas and the old man could be heard shouting at the foot of the stairs, ‘Get up, you bastards!’ A sequence of failures, it must have been a worry for the father.

With Ward’s teenage life becoming a shipwreck in the azure waters, he could sense the city beneath the house flooding, and sometimes he dreamed of fleeing to a forest. He could not reconcile the contrasting images of the early father with the later father whose excess flaws and eccentricities were tolerated by people because of his corporate status and eminence. He began to reject his father’s power and authority, and sought substitute idols to worship, since he was already locked into the business of worshipping. But he was discovering that he was too sensitive to be a protégé of anyone. He was a loner and a dreamer. And by the time he had reached the age of seventeen, he had a fragmented sense of self and a wish to die. He would lie on his bed nursing philosophy books, rolling tobacco, and listening to CDs of grunge bands sneering through the grill of taut electric guitar strings, and he would insist, ‘I’ll be dead by the time I hit twenty-one.’ When life was truly unbearable, he would seek refuge within passageways of the cobwebbed city beneath the house where he had once laboured as a child. He would stand amongst blown light bulbs, his vocal cords pulling tight whenever he moved his lips, the passageways yet to be cleared for his laughs to rise like balloons.

Carny's alive

From Page 88

The police officers sat down at a table beneath a forty-watt globe, clutching their beers. The Carlton police had rebuffed the publican since he had started charging for every drink. And although the publican’s conduct was taken to be a sign of anti-police, Carny had remained faithful to him. Carny had his own deal going.

‘Well, everything ran smoothly,’ said Carny. He had survived another day as if that was his job description. ‘It was hectic in the watch-house and you were busy on the van, but we did our jobs. No one’s got any cause for complaint. You’ve got to know how to piss people off properly. You can’t have files on you for neglect of duty. Last night we had a visit from the duty inspector. A young soldier came to the watch-house counter with half an ear hanging off.’ Carny sounded quite eloquent after a few sips.

‘Anyone charged?’

‘No, mate! The inspector confronted him. “What sort of man are you? What kind of soldier will you make in Afghanistan if you can’t even take a scratch?” The soldier walked out the watch-house door holding his ear on with blood. Mate, that’s what I call brilliant pissing off of paperwork.’ He grinned.

They picked up their drinks and shifted upstairs to the publican’s private lounge.

‘When I was in the old District Support Group,’ said Carny, ‘we were pursuing a Commodore with three young bucks in it. The road slopes, and then slopes again a short distance further on. Well, the suspects’ car hits the second slope and becomes airborne, and collides into a pole and the boys get killed. Boy-o-boy, when we hit the second slope we took off too. Everything went flying – batons, cuffs, folders – and Carny was ejected from the driver’s seat but Carny landed safely.’

Carny grinned again. His body was too taut to actually laugh. Ward laughed.

‘Carny landed safely.’ He swallowed another mouthful of beer and exclaimed, ‘Carny’s alive!’

Ward looked at Carny’s hands that were almost twice the size of his own, and it occurred to him that Carny referred to himself in the third person to avoid a guilty conscience.

He had lost count of how much they’d drunk.

‘Take Carny’s advice. Got to cover your arse. Proof is the only thing that can bring you undone. They tried to pin culpable driving charges on Carny but they never had the evidence.’

Intuitively, Ward felt that he had to stick with Carny. He wanted to be a survivor too. A couple more rounds and they staggered towards Stewarts Hotel, doing their best to maintain an even distance from the kerb. Stewarts was the recipient of two classes of clientele who had each marked out their territories. The dregs of society occupied the oblong Druggies Lounge with its dim lights nourishing illusions of mischief and rebelliousness. The police regularly took refuge from work in a smaller room crammed between the public bar and Druggies Lounge. The space was colloquially known as Coppers Corner, a square room with a tuckshop counter and a few bar stools, and an overhead fluorescent light coating each shift of boozy drinkers with sheen. Coppers Corner was the office where many an important law and order decision was made regarding the fate of Carlton identities. Much of Ward’s training for drafting statements and giving evidence had taken place there. ‘In order to get a conviction, sometimes you got to exaggerate the facts, brick in a defendant with false evidence.’

There was a sliding door creating a rigid border for the two domains. The socialising between these drinking worlds with the dividing sliding door was generally harmonious, and of course the police always had the numbers and the power if there was any disturbance or act of aggression.

‘What a team! You mentoring young Ward?’ said Sergeant Wheel, and there were cheers. After a while Carny and Ward were left alone with a detective from the Criminal Investigation Unit. He was a dissembled, cherry-faced paralytic relating stories to them about the detective senior sergeant plotting to throw him out of the job for sexual harassment of offenders and shonky paperwork, bitter that his days were numbered. You could tell it was affecting his mind. It was noted that he was a less frequent visitor to Coppers Corner. And that he was metamorphosing into a radical barfly on the other side of the sliding door, seeking solace from criminals, disbarred solicitors, junkies, civil libertarians and other lowlife, some of whom the detective had personally charged. He was consorting with his victims for succor, and maybe redemption. It was rumoured that while on sick leave he had helped out a local crim do an extension to a bush shack and that the activity was probably just another excuse to drink piss in anti-police company. Carny and Ward deserted the falling detective and drove in Ward’s car to the Classic Motor Show at the Royal Exhibition Building. They bluffed a free passage past security using their Freddies, swigged from a bottle of wine once back in the car park and then drove back to the hotel that the rest of the Carlton police had forsaken.

Ward spotted Allison, one of the barmaids. He’d slept with her a couple of times just before he’d met Phanta; been on the same sex run as many of the other male coppers. She’d finish up at the bar, then you’d drive her straight to the Fitzroy housing commission flats, go up twenty levels of concrete fearful of who might step into the lift, might be some docket-head you’ve charged. And then she’d lead you into her flat, a plasma TV at the foot of the bed already switched on, and a walnut dressing table with a circular mirror reflecting an upright bottle of whisky towering over perfume phials and glass jewellery boxes, the display looking like a model of a lustrous cityscape. You’d have sex to a late night repeat of Lost in Space, smacking together in a kind of passionless corruption that ends with the withering of your penis and her leaving you on the bed to dry as she slips into unconsciousness. And soon you’d also cut out, with the plasma continuing uninterrupted till dawn. And then she’d wake you up and you’d realise the TV’s been on all night displacing your dreams with new products. You’d realise that you’re not yourself and that’s why you feel shithouse, and she’d be happy that she’s helped you empty yourself because she knows you’re gonna come back for some more. And to Ward she had once said, ‘You’re nicer than all the others. Hollywood just has sex and walks out.’ And to that Ward had replied, ‘Senior Constable Hollywood’s pretty official about everything,’ and she’d retorted, ‘You’re very perceptive. I like you.’

He sought Carny’s opinion. ‘What do you think about her, about Allison?’

‘She’s a coppers’ mole.’

Allison was standing by the bar. Ward went over to her, couldn’t help himself; must have been drunk because he’d forgotten all about Phanta.

‘I want to come back to your place, Allison. We’ll have a bath. I’ll rub you down with soap and carry you to bed, switch on the plasma and fuck you.’

He placed his arm gently around her waist and kissed the concave mouth of her tiny face and forehead with its fringe of split ends. At first she succumbed but then came to her senses. She was still working.

‘Don’t, people are watching! You never came back after last time. Now you just have to wait. I’ve got a fireman staying with me tonight. Come on Tuesday. Here’s my mobile. Stick the number in your police shirt pocket. Don’t forget, this time.’ She pecked him on the cheek.

He returned to Carny. ‘She’s got someone from the fire brigade screwing her.’

‘Women love uniforms. Just about every bloke at the police station’s been through her. She’ll bring the place undone. Start an inquiry. The fire brigade can keep her, mate. Let’s go back to the station for a cuppa.’

White Anglo-Saxon Person

From Page 234

He waited till the end of the shift to consider his response. Once home, he could hear a voice that had been building up inside of him like a marching band. Trumpets and trombones of words were drawing nearer. A voice that was loud and clear began imploring him that only an ideology can realise a faith capable of completing the imagination of the self, unifying the past and the future into a set of pure truths, but it must be a supreme ideology. Is it capitalism, fascism, feminism, environmentalism, mediaism, consumerism, humanism, spiritualism, anarchism, transcendentalism, cultural-Marxism, multiculturalism? And just when all hope seemed lost, Ward realised that National Socialism is truly the answer and he knows that for sure. ‘So get dressed!’ the band sang out. Filled with blood-consciousness, he soon had a mouth-watering sense of his intrinsic cultural identity and he needed to defend that. He was a little afraid that he might be losing himself, but all chemicals in his body began to stabilise. He no longer needed to live in the shadow of instability, in fear of drowning in a psychic stream of nebulous reflections.

He was swiftly developing convictions and secret aspirations for the world about him as he walked down streets with trams rattling by, and horns tooting, and mouths opening and closing. He realised that he was an honourable person. He did not use the dead as bargaining chips. The dead are dead, the living confirmed. He belonged to Kubizek’s Club of Err. His faith would endow him with shared ideals and standards to take him as close to truth as he could get without getting burnt. He was an ethnic in Australia. Not superior to the Jew or the Arab or the Aborigine or the Negro or the Indian or the Mongol. His future resided with his own Nordic stock. It has been that way since the dawn of ages. He shouted with joy, ‘I am a white Anglo-Saxon person!’ And the world shuddered.

Case of the missing soap

From Page 258

He drove to nearby South Melbourne Police Station to collect from the Warrants & Files Officer warrants on a burglar he’d arrested. He acknowledged the watch-house keeper and headed upstairs to the mess room for a coffee. Somehow, the watch-house keeper beat him to the mess room and was already sitting at the kitchen table drinking from a mug.

‘How’d you get up here so quickly?’

‘That’s my twin.’

It was on that day he had got to know the Krüger brothers. But he could never tell them apart. The brothers were tall, beefy and stoical, and had the same thick spiky hair. They were the type of men who tend to keep their imaginations to themselves until they are ready to act. They were German.

On a later visit to South Melbourne, Ward was caught off guard as one of the twins began to explain to him that the Holocaust was a hoax. Ward could not tell which one it was, but it became obvious that despite their identical appearances, the Krügers had opposing sensibilities. Let us say, K-1 was an empathetic, shame-laden, social worker type, whereas K-2 was a helmeted, radical, intellectual denier.

‘The indoctrination of each generation of Germans to feel guilty for being German, it makes you want to make a stand,’ said K-2. ‘At the end of World War 2, Germany was converted into one giant concentration camp, and Germans weren’t allowed to fly in aeroplanes. The crimes committed against the Germans is a study in its own right of man’s inhumanity to man. And it makes you wonder why Germany is financing a Zionist state that has no capacity to stand on its own two feet yet is armed to the hilt with nuclear weapons?’

Ward acknowledged K-2’s frustrations, but otherwise he was not inclined to respond. He was concerned that the innocuous chat might be bugged, and he did not want to risk alienating himself from members of the police force again. It was only when Ward was blind drunk that he would ooze fascist traits.

‘We know what’s going on,’ K-2 continued. ‘My relations were supposed to have gassed Jews and turned them into soap and lampshades. It’s a load of horseshit! Just lies created at the end of the war by the gatekeepers to put a nail in the coffin of the German people.’

‘But I’ve seen the soap,’ said Ward, provocatively.

‘Where, man?’ said K-2 incredulously.

‘At the Holocaust Centre in Elsternwick. The oil base was supposed to come from Jewish fat. But what about the olfactory process for the scent?’ Ward asked.

‘Are you serious?’ asked K-2 sibilantly.

‘I’m joking,’ Ward replied.

'No people in history have been as severely punished as the Germans were after the war,’ said K-2.

The conversation with K-2 prompted Ward to revisit the Holocaust Centre on his way back to St Kilda. It had been about ten years since the school excursion there. He needed to see the soap on display in the glass cabinet once again. Rediscover his empathy for the Jewish people. For it seemed they have a tradition to thrive on calamitous events that demand a greater commitment to their covenant with God, whether they are the perpetrators or victims, and regardless of whether or not the soap was made from corpses many Jewish people have faith in its symbolism and that ought to at least be respected.

He pulled up in the police sedan outside the Holocaust Centre. The building had a sculptural façade of interwoven hands to maintain people’s collective memory. The large double doors took much strength for him to open, as if the building was afraid to expose the horrors within. He entered the foyer. There was a young man sitting behind the reception counter. His hair was thick and dark, his eyes almond-shaped with large upper lids, and with his protruding eyeballs he looked radiant as he asked the constable if he needed assistance.

‘I just want to do a tour,’ said Ward, trying not to blow his cover. ‘I came here about ten years ago. It’s changed a fair bit. It’s brighter with the stark white walls and the modern foyer.’

‘I don’t know. This is my first day. I’m a volunteer.’

His nose was narrow at the root but large and prominent as a whole, and he had a thick lower lip, giving him a sensual appearance.

Ward dropped $10 into the donation jar. He would now be able to see things differently from what he saw and understood as a vulnerable kid on a compulsory excursion. The first exhibit was a map of Europe with signposts across the terrain of countries highlighting Jewish populations, before and at the end of World War 2, amounting to the 6 Million deficit. He noted that there was no mention made of gentile deaths from the world war that ranged between 50 and 70 million. A student was crouched in front of the map assiduously copying down the figures. Beyond this gateway of numbers there was a sizeable display board with another map. This one was of Australia.

‘Oh, no, the guilt trip begins,’ he murmured.

Text that was large and bold stated that the Jewish Council in 1933 had made initial submissions to the Australian government to transfer to it 28,000 square kilometres of land in the Kimberley Ranges for colonisation by 75,000 Jews. The exhibit board recorded that in 1944 the war-time prime minister, John Curtin, finally announced that the government would not support the scheme, as Australia was a monocultural society and it would not depart from a long-established policy in regard to alien settlement. The vision for a Jewish territory in Australia was documented in the book The Unpromised Land by Isaac Steinberg, which was published in 1948.

The Kimberley scheme was a startling starting point to the tour. The first lesson of the Holocaust was that Australia had a history of abandoning the Jews. ‘Not guilty, Your Honour,’ Ward muttered. It occurred to him that maybe Aboriginal tribes, including perhaps Karin’s people, might have had an objection to their land being misappropriated a second time running. Also, big business may have had concerns given that a third of the world’s annual production of diamonds is now mined at Argyle and Ellendale, and oil is extracted from the Blina oilfield, with the region also producing gold, bauxite, nickel, copper, cobalt, iron ore, lead and zinc, and most of the world’s finest-quality cultured South Sea Pearls.

‘But on with the hoax tour!’

Wandering in and out of alcoves and bays searching for the soap of his childhood, he came to a halt near a guide. She was clumsily explaining to a blonde Jewess and her two daughters a large diorama of Treblinka death camp encased in glass, which she said to them had been built by a survivor. Made from materials such as polystyrene, plaster and plywood, it contained a miniature train set with a toy railway station, little trucks, long prickly threads for barbed wire, and thumb-size buildings with poignant chimneys the breadth of match heads, and a label next to one of the buildings that read Gas Chambers. Ward laughed at the childlike quaintness of the exhibit.

They turned towards the police officer. He smiled. ‘Sorry. I’m a visitor.’

The guide smiled back. ‘We have just celebrated the Holocaust and Genocide Film Event, so it has been a very busy week for us.’

Ward waited until the guide was by herself. ‘I came here about ten years ago. There was a block of human soap in one of the glass cabinets. Do you know where it is?’

‘I haven’t seen it. I haven’t been here long. I’ll ask one of the assistant curators.’

While waiting patiently, he explored an interactive StoryPod of survivors’ stories of murder, hunger and death, and inspected wall-size black and white photographic images of children behind wire fences, imposing portraits of Adolf Hitler in the company of Nazi heavyweights, and images of famished internees lying on bunks in cramped quarters coughing up smiles. He scrutinised name lists, and personal effects such as combs, brushes, spectacles, numismatics, jewellery, shoes, concentration camp uniforms, badges, armbands, but no soap!

A woman with a broad head, brunette hair and fair eyes approached him. ‘Can I help you? I’m an assistant curator.’

He examined her face more closely. It was round with prominent cheekbones and she had a broad nose with fleshy wings. Her outward appearance was quite Slavic; more European looking than the guy at reception.

‘I came here on a school excursion about ten years ago and there was soap made from Jewish fat in a glass cabinet. It affected me at the time, but I can’t see it!’

‘Actually,’ she replied to the police officer, with a heavy countenance, ‘I’ve done research into the soap, and in fact it is inconclusive as to whether soap was made out of Jews by the Germans.’

But Ward had always been a believer in the soap and no one, up until his recent disillusionment, had told him that it might be a fake story.

‘Survivors are not historians,’ she confessed. ‘We have all believed in the soap because anything was possible. But there is no factual evidence. We must be careful. We do not want to make claims nowadays that could be contentious given that there are Holocaust deniers around using modern technology to disseminate hate and bigotry and anti-Semitism. We have now become aware that the story of the soap was just propaganda used by the British to vilify the German military during the First World War. It was claimed that the Germans turned their dead soldiers into industrial fat, and it seems a variation on that story was spread during the Second World War. Poles used to taunt Jews at the camps that they would be turned into soap. Several years ago, I requested the Victoria Police Forensics to test for authenticity of the soap you saw. They provided me with advice that they have no test to determine whether the soap is made of human fat. One survivor brought in a blanket that he claimed to be from Dachau. I had that tested by the police and it did have some traces of human hair on it, which you can tell by the diameter of the hair, but once again there was no evidence that the blanket itself was made of human hair. In fact, it was made of horsehair. Survivors keep bringing in all sorts of things.’

‘So where’s the soap gone?’

‘It’s in storage upstairs. But I’m not sure exactly where. I haven’t seen it for awhile.’

He thanked the assistant curator for her time.

Germans transforming the stuff of human beings into lampshades, soap, blankets – all turns out to be folk tales.

‘But what are we left with?’ he asked himself. Pellets of Zyklon B, a pesticide for delousing clothing and which was the only effective means of controlling the spread of typhus, were allegedly dissolved in buckets of water and then transfused into communal showers through a variety of crude methodologies that do not make much scientific sense, nor practical sense if the intention of the Germans was to gas large numbers of people, and for which no forensic evidence has been produced anyway.

And once skinned of the macabre myth-making, what remains of the narrative: Jewish families hiding underneath houses, in cellars, and in attics, and mass transportation of Jews to labour camps, and typhoid, malaria, other diseases, starvation, and much death – maybe 750,000 Jewish deaths, but not the magical sum of 6 million – usual products of war.

He walked out of the Holocaust Centre. He dwelled on the thought that perhaps the real crime was reflected in the disturbed eyes of K-2 – the bricking in of the German nation for crimes it never committed. And what’s the motive for the falsehoods? There must be more than one reason for the Holocaust industry persisting, otherwise it would have shut down years ago. Multiple motives came to mind – financial compensation, revenge, anti-Europeanism, Zionism, eschatological linearism. And lest these tales should depart from the Jewish heart, they pass on the survivor-syndrome to their children, and to their children’s children.

He sat behind the steering wheel of the police car. He made a notation in his folder: The investigation into the alleged gassing of the Jews is concluded. No offence detected. Case closed. He signed his name off at the bottom with the upward flourish of a tick. He flipped his folder shut and slid it in between the console and the driver’s seat, and turned on the ignition. He had taken his investigation as far as he reasonably could. It was now official. He looked in the rear vision mirror. His insights fused together as the façade of clambering hands receded into the distance.

Chapter 38 (p281) - A new humanity is near

Ward had toured around the sun, the moon, and the stars twenty-six times. He had experienced the Big Bang for what it was worth. He had viewed life through a telescope. And already he was on his twenty-seventh trip. He wanted to die! But one only has one life so it is better to keep one’s aspirations in perspective ....

Kristallnacht - .... There was a demonstration outside the building, and the tall doors to it were closed. Ward could hear a voice, high and shrill, condemning Holocaust deniers, cyberspace neo-Nazis and anti-Semitic youth. It was overawing. He could smell the sweat and desperation of several hundred demonstrators crammed together in the narrow street as if unloaded from a freight train. He could see the flickering of cupped candles in pupils, and hair untidily combed as if they’d rushed to get to the demo. It was a social network of students, union organisers, priests, monks and rabbis, community workers, greenies, and politicians from the left and right, with many wearing the yarmulke skull cap showing respect for God above. He eavesdropped on these procreators of history as they chattered and rustled about, their shadows merging with brickwork and doorways, studios and bars, closed offices and clocks. He watched as they munched on bagels and sipped coffee from polystyrene cups. Sometimes when they jeered it was threatening to him. He was wary of them, was Ward Price. He saw how easily the public smothers others’ truths, how possessive and destructive modern democracy can become, and how overrated it is as it so often turns people to collective spite.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Holocaust_denial

Holocaust denial is the act of denying the genocide of Jews in the Holocaust during World War II. The key claims of Holocaust

denial are that the German Nazi ...

What is Holocaust Denial - Anti-Defamation League

www.adl.org/hate-patrol/holocaust.asp

Holocaust Denial is an Anti-Semitic propaganda

movement active in the United States, Canada, and Western Europe that seeks to deny the reality of the Nazi ...

12. Jul, 2013

Latest comments